(by Tim Hume, The Independent, 21 January 2012) Alejandro Cao de Benos – or ‘Zo’, as his comrades call him – is a devoted follower of the late Kim Jong-il and vigorously defends the North Korean government he represents.

(by Tim Hume, The Independent, 21 January 2012) Alejandro Cao de Benos – or ‘Zo’, as his comrades call him – is a devoted follower of the late Kim Jong-il and vigorously defends the North Korean government he represents.

As North Korea convulsed in grief last month with the passing of its Dear Leader, the rest of the world tittered nervously. For Zo Sun-il, a North Korean government spokesman in Europe, this made the bereavement doubly hard to take. While he mourned in isolation, his phone rang hot with calls from international media, who marked Kim Jong-il’s demise by gleefully rehashing the more remarkable claims put forward about him in state propaganda: that he was an influential trendsetter in world fashion; that the one time he picked up a golf club, he made 11 holes-in-one. That he didn’t need to defecate.

Zo took their calls, and seethed inwardly. “I found myself alone in the outside world,” he told me, days before Kim Jong-il’s funeral. “It’s so painful to hear words from people that are so completely ignorant. They broadcast these stupid cartoons of Team America, making a mockery out of the pain of the Korean people. This makes me even more angry and resolute to continue defending his honour.”

For comfort, Zo drew on memories of the man North Koreans viewed as a father, and who, unlike the vast majority of his countrymen, he had met personally. He recalled the horn-handled hunting knife he had presented Kim, and the tea set he had received in return. The way that Kim seemed to single him out for personal salutes at military parades. “His eyes looking at me, his face smiling at me. I keep this very dear to me,” he said.

Most of all, the way Kim’s words had guided Zo to reach his own improbable life’s goal: of joining the Communist revolution by becoming part of the North Korean government. “My friends would say, ‘We love you, but what you want to do is impossible’,” he said. “But in his speeches and writings, Kim Jong-il taught me that impossible is a word that doesn’t exist in the Korean language.”

Zo, whose name means ‘Korea is one’, had to take the Dear Leader’s word for that, because he doesn’t actually speak Korean. His friends’ scepticism seems well-founded given that he is a Spaniard of aristocratic Catalan heritage, better known as Alejandro Cao de Benos, and that North Korea is possibly the world’s most paranoid and isolated nation, a nuclear-armed rogue state all but closed to outsiders.

Yet despite this, Cao de Benos – or Zo – has managed to achieve the unique distinction of being granted honorary North Korean citizenship and an official role as “honorary special delegate” to its Committee for Cultural Relations with Foreign Countries.

He spends about half of every year in Pyongyang, where he has close ties with the upper echelons of the regime. There, he hosts foreign delegations and acts as an intermediary for external parties wanting to invest, make documentaries or simply visit the country. (He maintains he has “never received a single cent” from North Korea, although admits to clipping the ticket on deals he helps see to fruition.) The other half of the year he acts as a roving ambassador, making media appearances with each new flashpoint arising from North Korea’s nuclear brinkmanship, his talking points drawn from the state ideology of juche, or self-reliance.

A rotund 37-year-old with a brusque bearing (as a young man, he spent a year in the Spanish army), Cao de Benos speaks forcefully and formally, favouring archaic terms of statecraft like “plenipotentiary”. For public appearances, he wears a North Korean military uniform heavy with state medals, or black suits cut in the distinctive, high-buttoned style of his adopted homeland, from which his scrubbed, clean-shaven face emerges like a pink balloon.

It took a decade of wooing of North Korean officials before Cao de Benos, who has a background in IT, sought and received permission to set up the country’s first website, in 2000. “Imagine you’re bringing flowers every day to a girl and she’s always rejecting you,” he recalls.

The webpage he built established the first fixed, broadly accessible conduit for communication between North Korea and the world beyond its borders. “Imagine the power in my hands!” the webmaster marvels.

Although he had envisaged attracting “high profile people” – diplomats, entrepreneurs, journalists – Cao de Benos says the site was soon being used by “the most normal people in the world”, wanting to contact the DPRK (The Democratic People’s Republic of Korea). From their ranks, Cao de Benos founded the Korean Friendship Association, a club for people wishing to express solidarity with a totalitarian regime whose deadly famines, spontaneous acts of aggression and nuclear weapons programme has it viewed even by its closest remaining patron, China, as a dangerous liability.

On a Saturday afternoon last November, about 20 people assembled before the North Korean flag in a community centre in Camden, north London, for a meeting of the Korean Friendship Association.

Turnout was smaller than expected, given that Cao de Benos claims his organisation has 15,000 members, but the founder was unbowed. Flanked by a display of ideologically sound texts (sample title: “Kim Il-sung: The Great Man of the Century”), he seemed to be channelling his mentor as he delivered a stream of bellicose, anti-American invective.

“If they dare to touch a single inch of the DPRK, we will unleash all our force,” he promised. “If you shoot even one nuclear bomb over US territory, it’s enough to destroy the country,” he went on. “The people will start killing each other, because everybody has weapons in their houses… It will be the Far West once again.”

Though many in the audience wore militaristic attire, the impression was more that of a Boy Scout jamboree. At such meetings, KFA members are awarded badges and posters, and jostle to outdo each other with their trainspotters’ grasp of the minutiae of North Korean life.

Like other followers of niche enthusiasms – medieval role players, American Civil War re-enacters, Japanese anime obsessives – the KFA’s members seem not completely at home in their own world, seeking instead a deeper affinity with a distant, idealised time or place. For them, North Korea’s isolation, its status as a mysterious, forbidden kingdom in an otherwise globalised world, is the source of its unlikely mystique. “It’s the only exotic country,” explains Frank Martin, a 49-year-old Parisian bank manager and KFA member, who has twice visited North Korea on KFA solidarity tours.

North Korea is seen as the ultimate outlier, boldly defying not just global corporate capitalism, but modernity itself. Their fantasy worker’s paradise hews to simpler, nobler values than exist in the benighted West. “They’re not having an easy time of it, the Koreans, but what drives them? What keeps them going? How can they have such grit, whereas in the West they fold over any given problem?” asks George Hadjipateras, a 36-year-old London office clerk and ideological true believer whose affection for North Korea as Communism’s last great hope extends to collecting the republic’s music, and picketing the US embassy once a year. He doesn’t believe the “lies” he reads about Kim Jong-il in the Western media, but has never visited the DPRK because he doesn’t like to travel.

“Sarcasm doesn’t exist in DPRK,” Cao de Benos notes at one point, giving a list of things that do: “Honour, respect, order, discipline”.

Cao de Benos was a serious-minded teenager seeking a solution to the world’s problems, when he first found himself drawn to North Korea in 1990. “I didn’t want to dedicate my life to be a slave in the capitalist system. My dream was to be a part of the revolution,” he recalls.

When, at 16, he came into contact with a North Korean delegation at a World Tourism Organisation exhibition in Madrid, he was mesmerised. “They treated me as though I were their own son,” he recalls. Two years later, he made his first trip to North Korea, with money saved working nights at a petrol station. There, his infatuation deepened. “In DPRK, not only did I find a reflection of my ideal politics, but also of an ideal way of life. I was feeling I was half-Korean.”

In the following years, he developed close relationships with officials as high-ranking as Kim Yong-nam, the Chairman of the Presidium of the Supreme People’s Assembly, who in theory jointly ruled the country as part of a tripartite executive with Premier Choe Yong-rim and, before his death, Chairman of the National Defence Commission Kim Jong-il. (Like many things in North Korea, theory and practice surrounding this arrangement do not necessarily align: Kim Jong-il’s power was absolute.)

Cao de Benos’s fidelity to a rogue state has come at considerable cost. When his interest began, during the time of perestroika, he says, “saying you were a Communist was close to saying you were a terrorist”. He lost jobs and friends, upset his family, and became “a very isolated person”. But he says his convictions never wavered. “If I had taken a different path, in IT or politics, I could have enjoyed success much earlier and without problems. I wouldn’t be a millionaire, I’d be a billionaire. But I’m a revolutionary person. I had to go a very hard and painful way that no one else has taken.”

All the same, his work has earnt him a minor degree of celebrity in North Korea, where he writes newspaper articles and performs revolutionary songs at government banquets. “People will approach me with their babies if they see me in the street, or invite me for a drink,” he says. He makes no secret of the fact he enjoys the status his role as a gatekeeper affords him, in North Korea as well as beyond it, among media, businessmen and other curious parties seeking access to this closed-off regime. “Suddenly, I’m a very, very respected person, even among people who are not Communists.”

Not everyone agrees. Deploying a term historically used for Western sympathisers of the Soviet Union, a former participant on one of Cao de Benos’s tours to North Korea describes him as a “perfect example of the ‘useful idiot'”.

The one-time traveller – who does not want to be identified for fear of jeopardising future trips – had taken the tour out of a sense of goodwill and curiosity, “to see if North Korea could really be as bad as everyone said it was. It was”.

“You mostly just wanted to cry,” the tourist recalls. “It’s like you’ve witnessed a terrible car accident, and you slow down just enough to see, but you’re not allowed to do anything. And then you leave, and you know there’s no ambulance coming to help.”

The group witnessed events and settings that were clearly laid on for their benefit, and increasingly felt their presence was being mined for propaganda. Closely monitored, the visitors had no opportunity to discuss their concerns. Even after the tour’s conclusion, back in the safety of Beijing, they remained too shocked to dissect their surreal ordeal. The fakery was so obvious that the trip might have seemed farcical, were it not for the ominous sense that there could be terrible consequences if events deviated from the approved pathway – both for the group, and any North Koreans dragged into their gyre.

One such departure from the script was captured in a Dutch documentary, Friends of Kim, which follows a KFA trip to North Korea in 2004. During the tour, Cao de Benos breaks into the hotel room of an American journalist in the party, stealing his tapes and denouncing him to authorities. The terrified reporter, under threat of imprisonment, signed a confession and an apology for filming sensitive sites, and was allowed to flee the country.

Incidents like this have earnt Cao de Benos a reputation as a dangerous ideological brown-noser, eager to report on anyone whose actions might be politically suspect in order to curry favour with his superiors. Certainly, it was witnessing this type of behaviour which has led the former tourist to conclude: “In my view, he’s a narcissist. And he loves the power and control he has over there. He does have real influence. People are frightened of him, and he likes that power. I think his primary motivation is that he’s special there.”

For his part, Cao de Benos says he has no qualms about taking action against the journalist during the trip featured in the documentary. He would have been blamed if the journalist’s report had eroded the dignity of North Korea. To the best of his knowledge, while his denouncements have led to North Koreans being demoted in rank, no one has been sent to a prison camp as a result. Besides, he says, those camps – in which international human rights groups say 200,000 political prisoners are held in inhumane conditions, starved or worked to death or publicly executed – are not the great evil they are made out to be.

“These are re-education camps. With 24 million people, sometimes you may have a few criminals. We believe not in punishment but in rehabilitation. It’s a kind of psychological therapy.”

Another misunderstanding he is keen to clear up is that North Korea is a hereditary dictatorship. “There’s no one person that decides everything and can do whatever he wants,” he explained, two days before Kim Jong-il’s funeral. As to whether the dictator’s third son, Jong-un, would become “the next beloved leader of Korea, it is up to the people of Korea to recognise him as such”.

The people of Korea must have liked what they saw as, four days later, Kim Jong-un was formally named supreme commander of North Korea’s military, making the untested political novice, believed to be 28, the world’s youngest head of state.

Dr Leonid Petrov, a Korea specialist at the Australian National University, has had contact with Cao de Benos for more than a decade, and doubts that he, or any other rational outsider, could genuinely believe North Korean state propaganda. He believes the KFA president is making the right noises ideologically so that he can straddle both worlds, carving out a profitable niche as a middle man and deriving status, access, and financial rewards through his consultancy work.

“Alejandro believes that to be close to the establishment he has to play the role of a revolutionary Westerner who is more North Korean than the North Koreans are,” Petrov says. “I really doubt he is a brainwashed individual who believes North Korea is the paradise for workers. Even North Koreans don’t believe in that.”

“I don’t think he’d like to spend the rest of his life in North Korea,” he adds. (Cao de Benos responds that he would love to live in Pyongyang permanently, but that would prevent him from performing his spokesman role in the West.)

The member of his tour party agrees – “You can’t possibly believe that stuff if you’ve been there” – and says while believing state propaganda is understandable for brainwashed North Koreans, it’s unconscionable in a Westerner who knows the outside world.

“To come back and tell North Korean people that everything they hear is correct – that the rest of the world is evil, out to cut each other’s throats, that war and oppression is everywhere… he perpetuates that. He’s not forced to; he does that for personal gain and power and prestige. It’s horrible.”

Cao de Benos bristles at the suggestion he is motivated by anything less than genuine ideological commitment. “I will take this as a type of jealousy from people who have no goals in their life. I have lived a life of big things,” he reminds me. “I only care about the opinions of the people that love me, my comrades.”

Given his position, he need neither answer nor fear their criticisms from the West. And despite the recent upheaval, that position so far appears secure. Kim Jong-un is “a very military person” who is “exactly like” his father, he says, and who, most importantly, “represents the continuity of our ideology”.

“He’s an important sign that although Dear Leader Kim Jong-il is passed away, there’s not going to be any changes,” says Cao de Benos, perhaps hopefully. Whatever North Koreans might make of that, it suits him down to the ground.

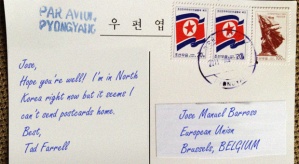

(NKnews.org, 20 February 2013) Western tourists in North Korea have been banned from sending postcards home to friends and loved ones, supposedly as a result of “sanctions” passed in recent days and weeks.

(NKnews.org, 20 February 2013) Western tourists in North Korea have been banned from sending postcards home to friends and loved ones, supposedly as a result of “sanctions” passed in recent days and weeks.

by MARK MacKINNON (Saturday’s Globe and Mail, Dec. 04, 2010)

by MARK MacKINNON (Saturday’s Globe and Mail, Dec. 04, 2010)

“Europe – North Korea. Between Humanitarianism and Business?”

“Europe – North Korea. Between Humanitarianism and Business?” By James E. Hoare (www.38North.org)

By James E. Hoare (www.38North.org)

Leonid Petrov (The Korea Times 11-27-2009)

Leonid Petrov (The Korea Times 11-27-2009)

Par Arnaud de la Grange, envoyé spécial à Pyongyang, (Le Figaro 20/10/2009)

Par Arnaud de la Grange, envoyé spécial à Pyongyang, (Le Figaro 20/10/2009)

You must be logged in to post a comment.